Oxygen Therapy in Pulmonary Fibrosis

Abstract

Pulmonary fibrosis (PF) is the chronic, progressive, and irreversible interstitial lung disease that is characterized by excessive lung parenchymal scarring, thereby reducing oxygen exchange, resulting in dyspnea, and eventually resulting in respiratory failure. Oxygen therapy remains among the most significant supportive management methods in terms of decreasing hypoxemia, enhancing exercise tolerance, and quality of life. Oxygen supplement has a significant positive effect on functional performance, reduces the morbidity of chronic hypoxia, and can potentially improve survival, but it does not alter the underlying pathophysiology. The paper is evidence-based and has addressed the nature, signs, and mechanisms, benefits, limitations, and clinical implications of oxygen therapy in pulmonary fibrosis.

1. Introduction

Pulmonary fibrosis is a set of interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), which result in scarring or fibrosis of the lung tissue. It is mostly also in the form of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) that has no known cause and most often affects the older population. PF is characterized by progressive thickening and stiffening of the lung tissues which further causes it to become progressively harder to get oxygen to the bloodstream. Later in the disease, there is a decrease in the amount of oxygen in blood which causes a condition called hypoxemia, fatigue and dyspnea.

As pulmonary fibrosis is irreversible and frequently progressive, the main objective of the treatment is to delay the disease process, manage its symptoms, and enhance the quality of life. Management of symptoms using oxygen therapy is also necessary in moderate-to-severe disease stages, despite pharmacological interventions such as pirfenidone and nintedanib, which reduce fibrosis.

When used correctly, oxygen therapy may reduce dyspnea, enhance physical exercise tolerance, and prevent such complications as right-sided heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. It is critical in patients with chronic hypoxemia in improving their physiological and psychological health.

2. Pathophysiology of Hypoxemia in Pulmonary Fibrosis

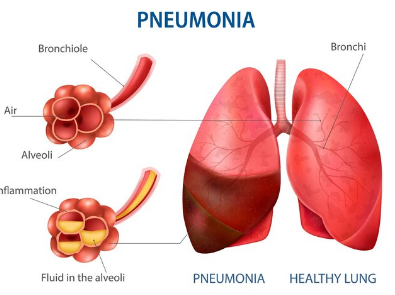

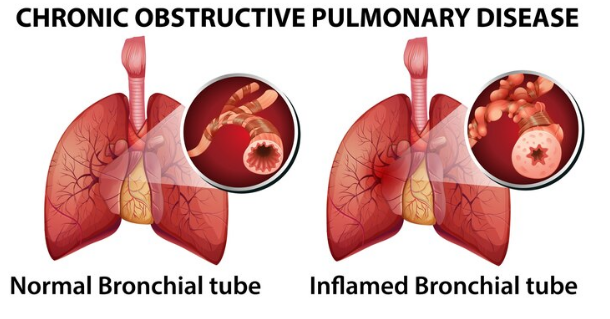

In pulmonary fibrosis, the alveolar walls become thick and scarred and inhibit the exchange of gases between the alveoli and the pulmonary capillaries. The destruction distorts the regular structure of the alveoli and reduces compliance of the lungs. Inefficient oxygen uptake to the blood leads to hypoxemia, which is especially evident during physical exercise or sleep.

The main reasons of hypoxemia in PF are the following:

1. Inefficiency of the ventilation-perfusion (V/Q).

2. Thickening of alveolar-capillary membranes which hinders diffusion.

3. Low oxygen in the mixed veins.

4. Shunting and hypoventilation in terminal disease.

Oxygen desaturation occurs even when resting because fibrosis continues to progress, which indicates the need of additional oxygen to maintain adequate tissue oxygen levels.

3. Indications for Oxygen Therapy

Oxygen therapy should be administered to patients who have recorded hypoxemia. According to the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the British Thoracic Society (BTS) clinical guidelines, treatment should be initiated in the following situations:

Resting hypoxemia is considered to be PaO 2 below 55 mmHg or SpO 2 below 88 percent on room air.

Exertional Desaturation: During exercise, SpO 2 reduces to 88.

Nocturnal Desaturation: Your oxygen saturation is less than 88% during more than five minutes when you sleep.

Early detection of hypoxemia is important. Arterial blood gas analysis and pulse oximetry should be used to determine the extent and trend of oxygen desaturation in patients.

4. Types of Oxygen Therapy

Oxygen can be delivered in different ways depending on the situation of the patient, his/her mobility and the oxygen requirements.

In the case of chronic resting hypoxemia, long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) is recommended in at least 15 hours daily. improves the quality of life and survival.

Desaturating patients at an effort level but not at rest can be given ambulatory oxygen therapy. allows the use of portable electronics.

Nocturnal oxygen therapy can be used in patients who desaturate during sleep and help in the reduction of fatigue and heart overload.

5. Oxygen Delivery Systems

Several equipments are used to successfully administer oxygen:

Prolonged comfort with a nasal cannula (1 6 L/min, 24 44% FiO 2).

Simple face mask (5-10 L/min, 40-60% FiO 2) should be used when oxygen needs are moderate.

Venturi Mask: Delivers a fixed oxygen concentration (4 -12 L/min, 24-60% FiO 2).

In cases of severe hypoxemia, non-rebreather mask (10-15 L/min, 60-100% FiO 2) should be used.

Oxygen Concentrator: Cheap and suitable in home therapy.

6. Clinical Benefits of Oxygen Therapy

The body will gain by having improved oxygenation and reduced dyspnea.

– Improves exercise tolerance.

Pulmonary hypertension is prevented. Improves cognitive efficiency and sleep.

Psychological Advantages: – Reduces anxiety and fear of dyspnea.

– Encourages socialization and self-reliance.

7. Risks and Complications

Even though it is generally safe, there are risks associated with oxygen therapy that include oxygen toxicity due to high flow.

There is a risk of fire because of its combustion.

Nares dryness and irritation.

– Irritation of the skin by cannulas or masks.

Psychological dependence or anxiety during the lack of oxygen.

8. Monitoring and Assessment

Keep an eye on stuff to make sure it’s actually working and not causing more problems than it solves. So, you’re looking at ABGs and using pulse ox to check SpO₂ and PaO₂. Oh, and there’s the classic six-minute walk thing to see if people’s O₂ levels tank when they move around.

If someone’s symptoms flip or just for the heck of it, check in again—every few months, maybe three to six, or sooner if things get weird.

9.Lifestyle stuff matters.

You get way better results if you mix supportive care and oxygen therapy. Pulmonary rehab? It’s not just a fancy phrase—actually helps people last longer doing everyday stuff. Eat well, too. Seriously, your lungs like it when you’re not living off chips and soda. Stronger muscles and all that.

Don’t forget vaccines. Getting sick just makes everything worse, so dodge that bullet if you can. If stress is turning your brain into mashed potatoes, talk to someone—a psychologist can help dial down the anxiety. And honestly, portable oxygen tanks? Total game-changer for getting out of the house and not feeling chained to your couch.

10. Recent Advances and Research

Honestly, oxygen therapy’s gotten way more user-friendly thanks to stuff like smart oximeters, those portable oxygen concentrators you see people carrying around, and better humidification (no more feeling like you’re breathing desert air). People are even mixing it up now—trying combos of oxygen, antifibrotic meds, and telehealth check-ins. Still experimental though, so don’t get too hyped yet.

11.What’s not so great about oxygen therapy?

Well, it helps with symptoms, sure, but let’s be real: it doesn’t actually cure pulmonary fibrosis or magically turn back the clock on lung damage. There’s also the whole hassle factor—lugging around equipment, the price tag, and honestly, feeling tethered to a machine isn’t anyone’s idea of freedom. Plus, it doesn’t replace your regular meds or treatments. It’s just one piece of the puzzle, not the whole game.

12. Conclusion

Honestly, oxygen therapy is kind of a game-changer for folks dealing with pulmonary fibrosis. It might not be some magic cure, but it actually lets people breathe easier, move around more, and just feel a little more like themselves. Pair it up with stuff like good food, emotional support, and rehab? Now you’re talking about a care plan that actually gets it. Sure, the disease isn’t going anywhere, but with oxygen, people can grab back a bit of independence and, honestly, just live with a bit more comfort and pride.