Pulmonary Fibrosis — ICD-10, Causes

Introduction

Pulmonary fibrosis is a dangerous lung condition that leads lung tissue to scar which slowly affects the lung capacity. This article describes the ICD-10 classification, etiologies, symptoms, diagnosis, the techniques of management, and the means of improving the results. It is also free of errors, properly organized and search engine optimized (semantic SEO).

ICD-10 Code for Pulmonary Fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis is among the ICD-10 Category J84: Other Interstitial Pulmonary Diseases. To be more specific: J84.10 — Unspecified ICD10Data+1 pulmonary fibrosis.

J84.112: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (a more specific subtype) ICDcodes.ai+2 Unbound Medicine+2

J84.1-Other fibrosic interstitial pulmonary diseases (a wider group) is also relevant. AAPC+1

It is best practice to use the most specific ICD-10 code that has medical documentation. The appropriate code in case of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) has been suspected and known causes have been eliminated is the J84.112 ICDcodes.ai+1.

What Is Pulmonary Fibrosis?

Pulmonary fibrosis is the thickening and scarring of interstitial tissue in the lungs, which makes it difficult to exchange gases and it reduces lung elasticity. Fibrotic (scar) tissue slowly replaces the normal morphology of the lungs.

This process has an irreversible effect of decreasing lung capacity. Fibrosis may be secondary (disease or environmental exposures or injury), or idiopathic (cause unknown). The characteristic features are dry cough and progressive dyspnea (shortness of breath). Wikipedia+2ICDcodes.ai+2

The alveoli are ruined, lung tissues become hard, and the blood oxygenation is worsened. This causes complications such as respiratory failure and pulmonary hypertension that eventually increases mortality.

Etiology & Risk Factors

The key causes and risk factors of pulmonary fibrosis are the following:

1. Idiopathic (no known cause): This is the most common in the disease variant, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

2. 3. Loss of exposure to the environment: inhaling dust, silica, metal fumes, wood dust, and agricultural dust.

4. 5. The use of tobacco increases fibrosis.

6. 7. Radiation or drugs: some type of chemotherapy, drugs or radiation to the chest may result in fibrosis (however they would fall under other ICD codes). AAPC+1

8. 9. Interstitial lung disease with fibrosis can be brought about by connective tissue or autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and scleroderma.

10. 11. The outcome of repeated lung injury or alveolitis or chronic inflammation is known as maladaptive repair.

12. Knowledge about risk factors helps in prevention, early diagnosis and differentiations of subtypes (idiopathic vs. secondary).

Clinical Presentation & Symptoms

Diagnosis is not easy at the beginning since individuals with pulmonary fibrosis often develop over time. Symptoms characteristic include Dyspnea, or progressive shortness of breath and initially during exertion followed by rest.

Coughing becomes dry, ineffective and gets more severe over time; fatigue, weakeness and weight loss, faint, velcro like crackles which are heard during the chest examination; and some patients may develop finger clubbing.

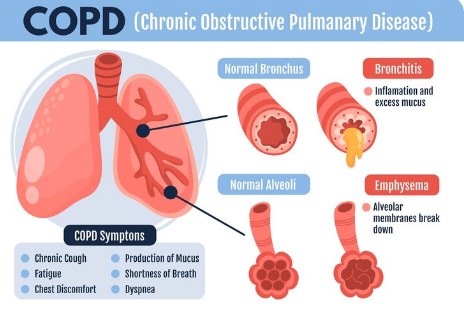

Misdiagnosis is common due to the possibility of the symptoms being confused with a large number of other respiratory issues, including asthma or COPD. The pattern of gradual worsening, changing appearance of imaging, and the elimination of reversible causes are important to determine.

Diagnostic Workup & Criteria

The process of making an accurate diagnosis is a systematic procedure which clinicians use to get to the correct diagnosis:

Review the medical history of the patient, consider whether he/she has an autoimmune disease, and eliminate other pulmonary disorders.

Two of the symptoms of pulmonary function tests (PFTs) are low diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO) and restrictive pattern (reduced total lung capacity).

The major method of imaging is a chest high-resolution CT (HRCT) scan. Examine traction bronchiectasis, basal-predominant reticulation, subpleural, and “honeycombing.”

Elimination of other causes: other causes such as environmental exposures, connective tissue diseases and infections are to be eliminated.

Where the pattern is not evident, it can be confirmed by a pathological lung biopsy or multidisciplinary discussion (e.g. usual interstitial pneumonia pattern).

The accurate documentation (HRCT findings, pathology, cause exclusions) is what makes the use of the most specific ICD-10 code (e.g. J84.112) possible. ICDcodes.ai+2 ICDcodes.ai+2

Requesting physicians to explain things is important since ambiguous writing presents the chances of misclassification.

Pathophysiology (How Fibrosis Develops)

Honestly, wrapping your head around how this disease works is the first step if you wanna figure out how to treat it. Here’s the deal: the tiny air sacs in your lungs (the alveoli) keep getting roughed up over and over again—think of it like the world’s worst groundhog day for your lung tissue.

Instead of healing up nicely, the repair system goes haywire. Instead of just fixing what’s broken, fibroblasts (these little repair cells) start multiplying like rabbits. Suddenly, you’ve got way too much collagen and extra-stuff crowding the space, which thickens and stiffens the lung walls. The whole architecture of your lungs? Yeah, it gets warped.

Oh, and the blood vessels aren’t off the hook either—they start remodeling, which can crank up the pressure in your lungs (pulmonary hypertension, not fun).

Bottom line: you end up with relentless scarring because of all these tiny hits and a totally botched healing process. And scientists are finding out there’s even more going on under the hood—genetics, molecular stuff like TGF-beta, and something called epithelial-mesenchymal transition are all tangled up in this mess. The more we learn, the weirder (and more complicated) it gets. Welcome to the frontlines of lung disease research.

Classification & Subtypes

Pulmonary fibrosis isn’t just one thing—there’s a bunch of flavors. The heavyweight champ is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), which basically means, “We have no clue why this is happening, but it’s definitely getting worse.” Classic.

You’ve also got fibrosis that tags along with connective tissue diseases—like, scleroderma can crash the lung party and leave a mess behind. Then there’s the kind you get from breathing in nasty stuff at work (think: silica, coal dust, or whatever else you probably shouldn’t inhale). Radiation or drugs can mess up your lungs too—like after a stint with chemo or radiation zapping your chest.

Some interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) just keep getting worse no matter what you throw at them. That’s what doctors mean when they say “progressive fibrotic phenotype.” Basically, the lungs just don’t take the hint.

If you know what type you’re dealing with—like, “Hey, this is idiopathic!”—make sure the code says that. If you’re clueless or the paperwork’s a mess, just slap on “unspecified” (J84.10) and call it a day.

Challenges & Common Problems

Pulmonary fibrosis is just a mess, honestly. People usually don’t even walk through the doctor’s door until the scarring in their lungs is already pretty bad—classic late arrival. And good luck figuring out what’s actually going on, since the symptoms look a lot like a bunch of other lung issues. Docs mix it up with pneumonia, COPD, asthma… it’s a whole guessing game sometimes.

And let’s be real, the outlook isn’t exactly rainbows. No magic cure, just some meds that kind of put the brakes on the disease, but don’t actually reverse anything. Plus those antifibrotics? They can wreck your day with side effects, not to mention the price tag—so you’ve got to figure out what each person can actually handle.

Keeping tabs on how fast things are getting worse is its own headache, too. At some point, you’ve got to decide if it’s time to talk about a lung transplant, which is a pretty big deal.

Bottom line, you need a game plan: detailed notes, teamwork with other specialists, and giving patients the real talk so they know what’s up. Otherwise, you’re just flying blind.

Management & Treatment Strategies

Look, there’s no magic bullet for pulmonary fibrosis—no “poof, you’re cured!” moment. But hey, that doesn’t mean you’re out of options. You’ve got a handful of ways to pump the brakes on the whole lung-scarring mess and actually squeeze out a better quality of life.

First off, let’s talk meds. For idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), there are these two main heavy-hitters: pirfenidone and nintedanib. They don’t exactly reverse anything, but they slow down the freefall, which is honestly a win in this situation. Some folks with other types of pulmonary fibrosis (like, say, the kind tied to autoimmune stuff) might get immunosuppressants or steroids thrown into the mix, but doctors aren’t usually keen on handing those out for plain-old IPF. And if you’ve got other issues tagging along—stuff like infections, high blood pressure in your lungs, sleep apnea, acid reflux—you’re gonna want those treated too. It’s basically a “whack-a-mole” situation with symptoms.

Then there’s the whole “supportive care” scene. Oxygen tanks? Yeah, they’re not exactly glamorous, but they do the trick for keeping your oxygen levels up. Pulmonary rehab is huge—think exercise, nutrition tips, and a bunch of education so you don’t feel like you’re flying blind. Don’t forget vaccines, either. Flu and pneumonia can knock you on your butt, so get those shots. Oh, and when the cough or breathlessness gets ridiculous, symptom management and even early palliative care can make a night-and-day difference. Don’t wait till things get ugly to ask for help.

If things get really dicey and you qualify, lung transplant might land on the table. Not everyone gets there, but for some, it’s a shot at a real reset.

And hey, if you’re the adventurous type, clinical trials are always looking for volunteers to try out the latest and greatest, like new antifibrotics or wild cellular therapies. Who knows, you might be part of the next big breakthrough.

Bottom line: The best results happen when you mix and match—think meds, rehab, symptom control, and planning ahead. And honestly, a little end-of-life planning isn’t morbid; it’s practical. Tailor all this to what kind of pulmonary fibrosis you have and what you can handle, and you’ll get the most out of whatever curveballs this disease throws your way.

Monitoring & Follow-up

Check in on how things are going: get lung function tests every few months, like three to six-ish. Toss in another HRCT scan here and there to see if the scarring’s getting worse. That 6-minute walk test? Yeah, keep doing that—it’s surprisingly useful for spotting changes in how much you can handle. Watch out for nasty side effects from meds, especially your liver, gut, and anything that might make you bleed. And if things suddenly go downhill, even while on treatment, don’t just sit there—time to talk about ramping things up or maybe even getting on the transplant list.

Prognosis & Predictors of Outcome

Pulmonary fibrosis—especially the beast that is IPF—is honestly pretty grim. If you don’t treat it, most folks have maybe three to five years. Yeah, not exactly uplifting news.

What makes things worse? A bunch of stuff, honestly. Older? Male? Lungs already not great? That DLCO number low? Things can go south fast. If your FVC is dropping like a rock or your HRCT scan shows a ton of scarring, buckle up. Toss in some heart issues or other health problems? That’s stacking the odds against you.

Doctors do have a few scoring systems to sort out who’s in the most trouble and who needs to get on the transplant list, like, yesterday. But it’s a rough ride, no sugarcoating it.

Problem-Solving & Best Practices for Clinicians & Coders

1. Be specific, seriously.

Don’t just jot down vague stuff like “lung fibrosis.” If you want to code for J84.112 (idiopathic) or nail down any other specific subtype, you need to dig deeper. Mention what caused it, what the scans show, and what the biopsy turned up. The more details, the better.

2. Don’t let fuzzy notes slide.

If you’re reading a chart and it says something like “interstitial lung disease with fibrosis”—yeah, that’s not clear enough. Time to ask: Did they do an HRCT? Any UIP pattern? Did they forget to mention the cause, or is it just not there?

3. Teamwork isn’t just a cheesy slogan—use it.

You want the right diagnosis? Get everyone on board. Radiologist, pathologist, lung doc… they all need to talk to each other. Nobody figures this stuff out solo.

4. Update codes when new stuff pops up.

So, maybe at first all you had was “unspecified fibrosis” (J84.10). But later, the workup screams “idiopathic.” Change that code to J84.112. Don’t leave it hanging.

5. Don’t skip the comorbidities.

If the patient’s got GERD, pulmonary hypertension, or any other baggage, put it in. It gives a better picture of how rough things really are. Plus, it helps keep the data honest.

6. Actually talk to your patients.

If they smoke, push them to quit. Help them tweak their lifestyle, make sure they’re sticking with their meds, and tell them not to wait if things get worse. Sounds basic, but a lot of folks need the reminder.

7. Don’t wait too long to think “transplant.”

If you’re watching someone’s health go south, don’t just cross your fingers. Get them referred to a transplant program before things hit rock bottom. Earlier is almost always better.

Pulmonary Fibrosis ICD-10: Here’s the Lowdown

Alright, so you’ve heard about this “pulmonary fibrosis ICD-10” thing and maybe you’re thinking, “Ugh, more medical jargon?” I get it. It sounds like something only doctors or insurance people care about. But honestly, it pops up more than you’d think if you’re dealing with lung issues or digging through your own health files. Here’s the deal: ICD-10 is just a fancy code system doctors use to name diseases. For pulmonary fibrosis, the magic number is J84.112. Not exactly catchy, but it comes in clutch if you’re filling out forms or just trying to make sense of what your doctor scribbled down. Not glamorous, but weirdly useful.

What Actually Is Pulmonary Fibrosis? (H2)

Alright, let’s break it down. Pulmonary fibrosis is when the tissue in your lungs gets all thick and scarred, so it’s harder to breathe. Not fun. It’s part of a crew called “interstitial lung disease with fibrosis”—basically, a bunch of lung issues where scarring is the main villain. Sometimes docs call it “idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” which is just a fancy way of saying, “We have no freakin’ idea what caused it.” Classic.

Why Should I Care About ICD-10 Codes? (H2)

First off, insurance companies are obsessed with these codes. If you want your treatments covered, you better believe you’ll need that J84.112 code written down somewhere. Plus, ICD-10 codes help docs track diseases, see trends, and, you know, not mix up your diagnosis with someone else’s. If you’re curious about other lung stuff, check out our page on interstitial lung disease.

Management of Pulmonary Fibrosis: Not a Walk in the Park (H2)

Let’s be real—managing pulmonary fibrosis is rough. There’s no magic pill. Docs usually throw a bunch of stuff at it, including:

– Meds to slow down scarring (like antifibrotics, if you wanna get technical)

– Oxygen therapy (yep, tanks and tubes and all that jazz)

– Pulmonary rehab (think: breathing exercises, not a boot camp)

– In serious cases, lung transplantation (which, yeah, we cover in more depth over here)

Honestly, if someone told you it was easy, they’re lying.

Living With Interstitial Lung Disease With Fibrosis (H2)

People living with interstitial lung disease with fibrosis deal with a lot. The shortness of breath can be a real party crasher, and the cough? Annoying as heck. There’s a whole support network though—docs, nurses, and even online forums where folks swap tips and vent. If you need more details, our interstitial lung disease hub is packed with info and resources.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: When the Cause is a Mystery (H2)

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis gets its name because, honestly, nobody knows why it starts. It’s like the medical version of “shrug emoji.” But once it’s there, the treatment path is pretty similar to other types—manage symptoms, slow down the damage, and keep an eye on your quality of life.

Quick Recap: Pulmonary Fibrosis ICD-10 Basics (H3)

– ICD-10 code for pulmonary fibrosis: J84.112

– Falls under interstitial lung disease with fibrosis

– Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis = cause unknown

– Management involves meds, oxygen, rehab, maybe transplant

Wanna dive deeper? There’s loads more on lung transplantation and interstitial lung disease elsewhere on the site. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, you’re definitely not alone. Take it one breath at a time.·

Sample Full Article Outline (for SEO)

Alright, let’s break this down like a real person would, not some medical textbook robot.

So first off, what’s the deal with pulmonary fibrosis? Basically, it’s when your lung tissue gets all thick and scarred up, which—spoiler alert—makes it tough to breathe. Not exactly a party for your lungs. The ICD-10 code for this is J84.1, in case you’re the type who likes medical trivia or has to deal with insurance forms (yikes).

Why does it happen? Oh, there’s a laundry list. Sometimes it’s from breathing in nasty stuff at work, or maybe you had an infection, or your immune system just decided to go rogue. Sometimes? It’s a total mystery. Doctors call that “idiopathic,” which is fancy for “we have no clue.”

People with pulmonary fibrosis usually notice they’re short of breath, like, way sooner than makes sense. Cough that won’t quit? Yup, that too. You might start skipping flights of stairs. Eventually, even tying your shoes feels like a workout.

How do docs figure this out? They’ll run you through a bunch of tests—lung function stuff, high-res CT scans, maybe even a biopsy if they’re feeling extra thorough. There’s a whole checklist.

Inside the lungs, what’s actually happening? The tiny air sacs (alveoli, if you wanna get nerdy) get replaced with scar tissue. Think of it like trying to breathe through a sponge that’s turning into cardboard. Not ideal.

There are a few different flavors of this disease. The classic one is “idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” but there are other types, like those caused by autoimmune diseases or certain drugs. Naming them all is a real alphabet soup, honestly.

Biggest headaches? Well, the scarring doesn’t really go away. Treatments can slow it down, but there’s no magic fix. Oxygen tanks, meds, maybe a lung transplant if you’re lucky and can handle it. Some folks end up with complications like infections or, worse, heart problems because their lungs tap out.

Managing this is basically about slowing down the damage, keeping symptoms in check, and trying to dodge complications. There are new drugs—pirfenidone, nintedanib—that help some people. Pulmonary rehab is a thing. And you’ll be on first-name terms with your lung doctor.

Docs keep tabs on you with regular checkups, breathing tests, scans, all that jazz. It’s a team sport.

Prognosis? Not gonna sugarcoat it, it’s a serious condition. Some folks do okay for years, others decline fast. Depends on the type, how early it’s caught, and what caused it.

Best advice? Get an early diagnosis, follow your treatment plan, don’t skip appointments, and if something feels off, speak up. Oh, and try not to Google too much—it’s a rabbit hole of doom.

That’s the rundown. Pulmonary fibrosis: tough break for the lungs, but with the right care, you can still keep moving.

Conclusion

Pulmonary fibrosis is no joke—it’s a nasty, progressive lung disease that can be a real death sentence if you’re not careful. And, look, when it comes to coding this thing in the medical world, you can’t just slap on any old ICD-10 code like J84.10 or J84.112 and call it a day. You’ve gotta get specific, or insurance and treatment go sideways. Coders and doctors actually need to talk to each other (wild, I know) or else the paperwork’s a mess and, honestly, patients lose out. There’s no magic bullet cure right now, which sucks, but folks can still get their lives back on track a bit—stuff like pulmonary rehab, antifibrotic meds, even getting on the transplant list early can slow things down and help people breathe a little easier.